Metering is related to exposure in photography, but it’s different. Exposure is the sum total of your camera’s aperture (how wide open or closed the lens is), shutter speed (how fast or slow the shutter opens and closes), and sensitivity. Sensitivity can be the film speed setting, measured in ISO values, or a digital camera’s ISO setting. Lucky for us film speeds and digital ISO settings are for the most part the same.

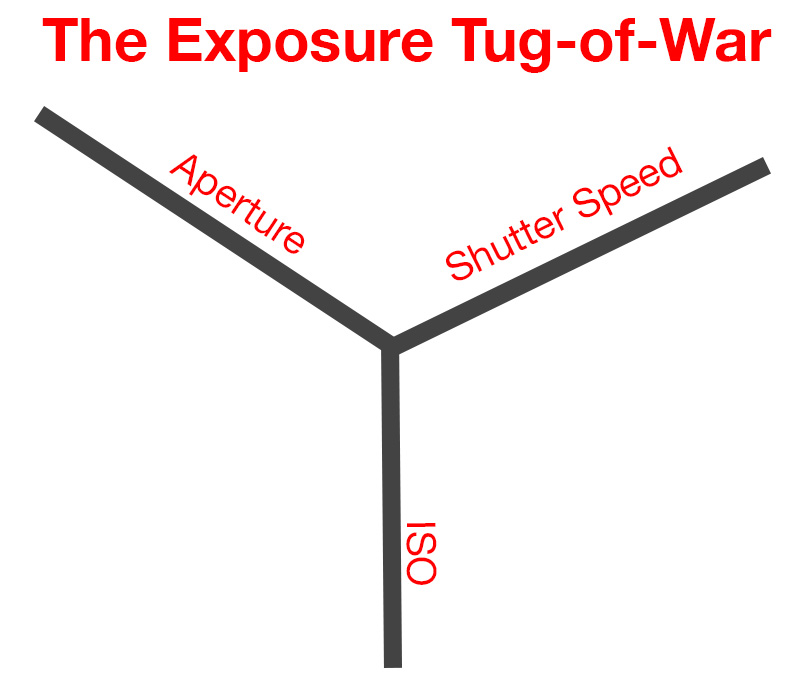

Many people describe exposure as a triangle. You may frequently be told to learn the “Exposure Triangle” and in some ways, this makes sense since the three values work together to contribute to the “proper” exposure value. We will discuss this in a bit. But I like to think of it as three strings tied together playing tug of war with the goal of keeping the knot in the center. If one side, say aperture pulls harder, the knot will slide out of the center. The other two strings have to pull back to get the knot back in the center.

Metering is the way a camera measures if the knot is in the center. Coming from film, you really never changed the ISO unless you changed rolls of film. Film photographers would just set the ISO for the film and only worked with Aperture and Shutter speed to keep things centered. Digital allows us to change ISO on every shot so you have a third item contributing to the overall exposure that you have to get “right”. More on “right” in a bit too.

Cameras have built-in light meters that attempt to measure the amount of light hitting the sensor (or film, we will just refer to film as the sensor from here on). Most cameras have three types of built-in meters:

- Spot Meter

- Center Weight Meter

- Matrix or Evaluative Metering (this term varies by camera maker)

There may be others, but these are the common ones.

Spot metering takes a small area of the viewfinder to take the measurements. Older cameras this was in the center of the frame. Newer cameras can move the spot with the autofocus point giving you more control. Spot metering is likely the most accurate form, but it’s the mode you have to think about the most and actively control. You have to decide what part of your scene is “Middle Gray” and meter on that to get the proper exposure. But it’s precise.

Center Weight metering involves using more of the frame to determine the exposure. Typically pulling from the center, the middle gets a higher importance, but the edges get factored in as well. The amount varies, but a typical center weight might give the center 2/3 of the scene and it gets 66% of the exposure calculation. The outer 1/3 contributes the other 34%. The size of the center can vary and the amount the center and edge contributes also varies.

Matrix metering looks at the whole scene and it’s broken up into an array of areas known as cells. The camera reads the value in each of the cells. The camera’s computer is able to take those values and compare them to an internal database of known scenes to find the proper exposure. In theory, matrix metering can detect tricky scenes like at the beach or a snowscape and expose them properly. It’s not 100% perfect, but it generally is the best metering mode for general use.

Digital cameras give you a fourth metering type, sort of. You get a digital histogram that shows you how many values of each tone in the image is present and graphs that out. Blacks are a value of 0. Whites are a value of 255. Middle gray is 127. You look at the histogram, after taking the photo pre-mirrorless, or before you take the photo with mirrorless. On a normal scene, most of the tones should form a hump in the middle of the graph.

But what does all that mean? Let’s start with a few terms.

Middle Gray — This is also commonly known as 18% gray, which has to do with how many black ink dots needed to be printed using half-tone dots to represent middle gray. In digital, we typically measure 0 as black and 255 as white, therefore the middle is 127. The camera will take whatever meter mode you are in and try to come out with a value that averages the scene to be in the middle. Most of the time this is good.

But it’s not always. Some scenes like snowscapes and sandy beach shots are in themselves brighter than middle gray and when the camera sees all that brightness, it will cause the camera to make that white snow gray in the image. If you’re trying to photograph a bride in a white dress against a black wall. The camera will see all that black and want to make it gray and you’re bride will be blown out. As a photographer, you need to recognize these situations and adjust your exposure as necessary. That means you may have to tell your camera to intentionally underexpose the scene or intentionally overexpose the scene.

In your camera’s viewfinder will be a gauge that shows you what the camera thinks the exposure is. If you’re shooting in any automatic mode, where the camera is controlling at least one of the exposure triangle values, that gauge should always read 0 or be centered. Older cameras would have a needle dial or just show a + or – if you were over or underexposed. Modern cameras will have something that looks like this: -2—-1—0—1—2 and a pointer somewhere in the area where the exposure is.

If you’re in manual mode, you are controlling all the aspects and you use this gauge/meter to try and adjust your aperture or shutter speed to get the pointer to 0.

Middle gray isn’t always the right value. You may want to intentionally have a photo overexposed or underexposed for various reasons. Sunsets are typically underexposed 1-2 stops to bring out the rich colors in the sky and take the super-brightness of the sun out of the equation. You might want to intentionally overexpose to create a high-key look. Bird photographers will sometimes intentionally underexpose their birds to keep the white on birds with detail and then boost the dark areas in post-processing to bring back that detail. It’s up to you, the photographer, to determine what “right” is.

If you’re shooting in an automatic mode, you can get the camera to intentionally over or underexpose a scene by dialing in a bias into the meter. This is done with the EV+/- button, typically located somewhere near the shutter release. This way you can still use modes like Aperture Priority or Shutter Priority and still correct the camera when it’s wrong.

Camera meters have an inherent flaw. They don’t actually measure the light on a subject. They measure the light entering the lens. As an example, if you’re shooting a high school basketball game. Part of the time, the players will have a brown set of bleachers behind them. Other times, there may be a white wall behind them. However, the light actually falling on the players is the same. If you depend on the camera meter, your exposures will be off.

Historically, photographers would use a hand-held meter, go on the court before the game and measure the actual light. Then in manual mode, they would dial in the aperture and shutter speed to set the values and use that for the entire game. Today you don’t see people using hand meters as much unless they are using studio strobes. Instead, they will use spot metering and find something that is middle gray in the scene and adjust their settings to that value or look at the histogram and adjust accordingly.

Histograms are a really cool feature we get with digital photography. You can look at your scene and see if you have a high contrast scene. The histogram will have a lot of dark tones and a lot of light tones. You won’t necessarily get a hump in the middle. If your peaks on the graph match up with what you see, then you will have a good exposure.